By Sarah Anderson, PhD

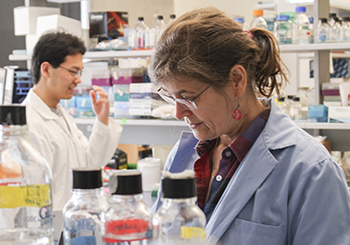

The Department of Microbiology and Immunology and the greater UBC community celebrate the career and retirement of Professor Pauline Johnson.

Dr. Johnson earned her bachelor’s degree in biochemistry at Liverpool University and her PhD in biochemistry at the University of Dundee. She was introduced to immunology research during her first post-doctoral position at Oxford University, where she studied the function of carbohydrate molecules on the surface of lymphocyte immune cells. “That got me hooked,” Dr. Johnson said. “With biochemistry, it’s like, ‘Here’s a Krebs cycle; here’s all the enzymes.’ With immunology, it’s like, ‘Here’s a box. There’s nothing in it.’ That’s what really drew me to immunology. There’s still loads we don’t know, and it’s relevant for all diseases.”

Dr. Johnson committed to a career of wrestling with the empty box, pursuing additional post-doctoral immunology research at the Salk Institute in southern California before joining the faculty at the Department of Microbiology and Immunology at UBC in 1991. Her research focused on exploring how proteins expressed on the surface of immune cells — namely CD44 and CD45 — help to orchestrate the immune response. After establishing that CD45 is critical for activating T cells, Dr. Johnson investigated the effects of binding between CD44 and the extracellular molecule hyaluronan. Uncovering key evidence that CD44-hylaronan interactions serve to regulate macrophage activity, she went on to study how this dynamic contributes to infection, inflammation, and metastatic cancer in the lungs.

Rather than one “claim to fame” discovery, Dr. Johnson characterizes her research career as having made progress in several important areas. “Science is built on people's shoulders. There's so many involved; there's so many contributions. And you don't always see at the beginning what it's going to lead to,” she said. “It’s more fun, following where your research leads you and broadening your horizons.”

In remaining open to unexpected directions for her research, “Pauline was never restricted to a specific disease, organ, or tissue. Because of this, she gained a wide-ranging expertise in understanding how immune cells signal and function, whether in disease or in healthy state,” said Asanga Weliwitigoda, a former PhD student of Dr. Johnson and Senior Scientist at Bristol Myers Squibb.

Stepping into her role as a research advisor was something Dr. Johnson learned on the job and approached by trying to instill her scientific values in her graduate students. “Scientific rigor is really important to me,” she said. “Attention to detail, reproducibility, being able to read a paper and critically evaluate it, problem solving, experimental design, making sure you have appropriate controls, analyzing data carefully, having the highest integrity — those are things that I value.”

Dr. Johnson regularly spent hours meeting with her students one-on-one, poring over data, troubleshooting experiments, and brainstorming next steps. “She set high expectations, encouraging everyone to work hard and strive for their best, but she was also incredibly understanding and flexible and always open to feedback. This combination of pushing us to excel while showing empathy created an environment of mutual respect and collaboration,” said Dr. Weliwitigoda.

Beyond PhD progress and publications, Dr. Johnson took a special interest in her students’ personal development, offering guidance that was tailored to each individual’s needs. “Everybody has strengths, and you work with the students to help them enrich their strengths, and if they've got weaknesses, to help support them in those,” she said.

Jackie Felberg, a former PhD student of Dr. Johnson and Senior Director of Program Management at Bio-Rad Laboratories, shared, “For my part, I was very shy and not comfortable with meeting new people or talking in front of groups. Pauline coached me on becoming more confident, provided numerous opportunities to present my work to lab mates in regular lab meetings, and sent me to many meetings and conferences on my own where I presented my work. Because of that early mentoring, I am now a confident public speaker and successful leader, not shy to speak my mind. I truly believe that I am the scientist I am today because of Pauline's guidance, mentorship, and encouragement, and I owe my successful career in large part to her.”

As she advanced to full tenured professor, Dr. Johnson extended her mentorship to faculty members newly navigating the demands of academia. “The biggest gift of having Pauline down the hall from my office was the generosity of her time. I benefited from it directly countless times when I hit the proverbial wall and remembered to reach out for help,” said Lisa Osborne, a professor in the Department of Microbiology and Immunology. “Pauline’s open door and counsel helped shaped my mentoring philosophy, decisions about where and how to spend my time, funding opportunities to pursue and experiments to do. …But more broadly, Pauline’s open door showed anyone who was looking how much she mattered to so many people.”

The heavy traffic in Dr. Johnson’s office is partly attributed to the fact that she was exceptionally invested in the success of students outside of her own research lab. She served as the department’s graduate and post-doctoral advisor for five years and was a member of a total of 136 thesis committees. “You don’t get a lot of credit for being on graduate student committees, so you do it because you enjoy it,” she said.

Taking on tasks for the benefit to the scientific and student community rather than for the recognition is a recurring theme for Dr. Johnson. She authored many grants to support the flow cytometry centre and other shared facilities and, determined to use research funds resourcefully, carefully maintained equipment in good condition. She was a lead applicant on the ImmunoEngineering NSERC CREATE grant, which established a professional development program for graduate students pursing research in immune-based engineering technology or therapeutics. The grant also supported Dr. Johnson in developing and launching new courses for microbiology and immunology graduate students that provide technical instruction and experiential learning in flow cytometry, experimental preclinical models, data science research, and teaching and learning practices.

As she embarks on her retirement, Dr. Johnson welcomes the freedom to be more in control of her schedule — although it won’t necessarily be any less full. She plans to continue to support graduate student education through the CREATE program and has a long list of hobbies to pursue: “I’d like to do more photography, gardening, I might learn Portuguese, I might help at a farm that I live next door to, I have a new puppy who’s a terror and needs training… I also have to keep fit to be able to handle him, so I’ll exercise at the Osborne Gym with my changing aging class,” she said.

Reflecting on her time in the department, Dr. Johnson said she will most miss working so closely with enthusiastic and driven students. “When you retire, you tend to look back as well as forward, and I think what I've really enjoyed is students who share the same passions as you,” she said. “If you’re passionate about science and immunology and research, and you meet somebody else who is, it’s awesome. You’re like, ‘What about this? What should we do about that? How are you doing this?’ And I just love it.”